‘Fiction was invented the day Jonas

arrived home and told his wife that he was three days late because he had been

swallowed by a whale.’

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez

From that point on, fiction has had quite a journey. In Spanish, it stops

to admire the view twice. Notably with the 16th century Miguel de Cervantes (29

September 1547 – 22 April 1616), whose

‘Don Quixote’ is regarded as the greatest work of fiction in any language. And,

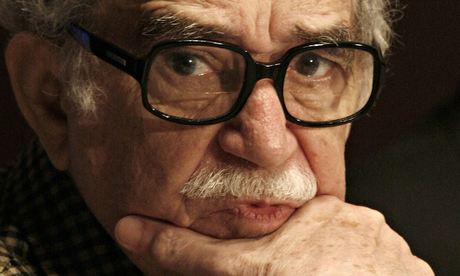

more recently, with Gabriel García Márquez, who died last night (April 17th

2014) after being treated during the month for dehydration and infections at a

Mexican hospital.

|

Gabriel García Márquez in Monterrey in 2007. Photograph: Tomas

Bravo/Reuters

|

The Colombian’s significance is evident from the familiarity of “One Hundred Years of Solitude" and "Love in the Time of Cholera", works that ring a bell even for the not-so-avid readers. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982.

They’ll be flying the flags at half-mast all across Colombia as President

Juan Manuel Santos declared three days of national mourning. Strangely, it’s

not the first time that the world has prepared to mourn the loss of the

literary giant. In 2000, a poem was disseminated that convinced all that

Marquez had, or was just about, to pass away. It was a hoax, but it made many

realise how much they should treasure him.

‘What matters in life is not what

happens to you but what you remember and how you remember it.’ - Gabriel Garcia Marquez

‘It is not true that people stop

pursuing dreams because they grow old, they grow old because they stop pursuing

dreams.’ - Gabriel Garcia Marquez

‘A person doesn't die when he should

but when he can.’ – 100 years of Solitude

Personally, I have yet to discover the extent of the rich quality of his

works, but I will always remember him. Every year. On April 18. When I recall

the morning I learned of his passing - my 27th birthday.